Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) causes benign tumors and cysts to develop in many organ systems, including the lungs. Wherever such lesions occur in the body, they tend to crowd normal tissues and, in some cases, inhibit organ function. Lesions that form in the lungs can lead to a lung disease called lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) that can profoundly compromise the lungs' ability to supply oxygen to the body.

Women with TSC stand the greatest risk of developing TSC-related lung abnormalities. Despite the prevalence of lung involvement among women, the majority of these cases remain asymptomatic, meaning that the lesions have no impact on lung function. Only about 1 to 3 percent of women with TSC develop cases of LAM that compromise pulmonary function, causing such symptoms as chronic and progressive shortness of breath and lung collapse. Despite the low incidence of severe complications, the health risks posed by these symptoms make LAM a legitimate cause for concern among women with TSC.

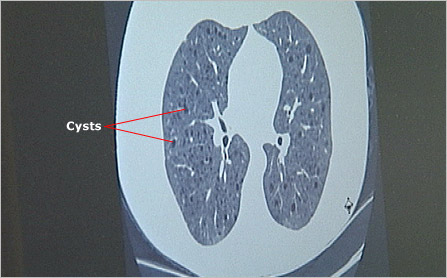

As the name suggests, lymphangioleiomyomatosis is caused by the excessive growth (matosis) of abnormal smooth muscle-like cells (leiomyo), also called LAM cells, around the bronchial tubes, blood vessels (angio), and lymphatic vessels (lymph) of the lung. As these cell masses grow, their impact on lung function becomes more pronounced. The tissue becomes pockmarked with pulmonary cysts. These air- or fluid-filled sacs crowd functional lung tissue and further reduce pulmonary efficiency. Cysts can also rupture, causing much more serious complications, including lung collapse.

Specialists aren't certain why women with TSC stand a greater risk than men or children of developing LAM. However, the predominance of LAM in women and the disease's relatively late onset have led some researchers to conclude that the hormone estrogen plays a role.

Diagnosis

LAM typically affects women of childbearing age. The average age of onset among women with TSC is 30 years. The most common symptom is shortness of breath, particularly during exertion. This symptom typically worsens over time as a result of the proliferation of and damage caused by LAM cell masses and cysts in the lining of the lung.

For some, the first sign of LAM is a collapsed lung, also called a pneumothorax. This occurs when a cyst ruptures, creating a small hole in the lining of the lung. The rupture allows air to escape into the surrounding chest cavity, and causes the lung to collapse. A pneumothorax requires immediate medical attention, involving removal of air from the chest cavity to allow the collapsed lung to re-inflate.

To better predict such severe complications, TSC specialists periodically examine the lungs of adult women with TSC using high-resolution computed tomography (CT). Images from these scans allow physicians to see existing LAM cell masses and cysts. Periodic exams enable doctors to track the size and number of these lesions to determine if the disease is progressing and requires treatment.

LAM is a major feature in the diagnostic criteria of TSC and, in some cases, provides the first indication of the disorder. More often, however, those who develop LAM have already been diagnosed with TSC and their lung involvement has been carefully monitored.

Periodic chest exams may also reveal another pulmonary manifestation of TSC, but fortunately one that does not produce clinical symptoms. Multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia (MMPH) may appear in CT scans as lumpy, or nodular, lesions in the lining of the lungs. These growths may resemble lesions associated with LAM. However, they present little cause for concern.

Follow-up and Treatment

Because of the risks LAM poses to a small percentage of women with TSC, specialists strongly recommend that all women with TSC undergo regular high-resolution chest CT scans beginning sometime before the age of 18, or at the time of TSC diagnosis for women older than 18. The initial CT scan establishes a baseline against which future exams can be compared to determine if the disease shows any signs of progression. It is also common for physicians to test the breathing capacity of women with TSC as part of their regular checkup. These screenings can help identify problems and provide opportunities to prevent some complications or treat them before they worsen.

Treatment options for LAM vary widely in their effectiveness and the ease with which they are administered. In general, they fall into two categories: those given to manage the symptoms or complications of the disease, and those given in an effort to slow LAM's progression.

To manage the symptoms of LAM, people diagnosed with the disorder are typically advised to follow a regimen of regular exercise as well as a healthful lifestyle, which includes not smoking. Physicians also recommend that people with LAM be vaccinated against influenza and pneumococcal pneumonia to help prevent respiratory infections. To relieve minor breathing difficulties, people with LAM can use inhalers typically used to treat asthma. However, more invasive medical procedures may be necessary to manage the complications associated with LAM. These include procedures to reverse a collapsed lung. In rare cases, lung transplantation becomes necessary. As of 2006, this is the only effective treatment for cases of advanced LAM and severe pulmonary complications.

Although scientists aren't certain what role the hormone estrogen might play in LAM, recently they have found that LAM cells have estrogen receptors in their cell membranes. This suggests that the hormone may somehow stimulate these cells to proliferate. Researchers are now treating cases of LAM with hormones, such as progesterone, that reduce the release of estrogen, as well as medications, such as tamoxifen, that block the effects of estrogen, to see if these therapies have an effect on the progression of the disease. However, because LAM is relatively rare, and sample sizes from these studies are small, the effectiveness of hormone therapies has been inconclusive so far. As of 2006, it was not known if this type of therapy has any significant long-term benefit in the treatment of LAM.

The link between LAM and estrogen presents a serious risk to women with the lung disease who wish to have children. Pregnancy causes a dramatic increase in the level of estrogen in the body, which has been shown to cause a progression of LAM in some women. Specialists often advise women with LAM to avoid pregnancy. As a result, those who have been diagnosed with LAM should consult with their physicians before getting pregnant. Doctors also recommend they avoid taking estrogen from sources such as birth control pills, which contain the hormone.

Researchers are also conducting clinical trials on a promising drug called Rapamycin. Researchers think that Rapamycin may prevent the damage caused by TSC by helping cells that have lost the ability to limit cell growth regain that control. If a drug such as Rapamycin is effective in restoring control of cell growth, it may help to slow or to stop the growth of lesions in any organ, including the lung. (For more information about clinical trials, see Research.)

Laurie, profiled in the TSC Family Stories section of this site, has lung and kidney involvement and is participating in the Rapamycin trial.

Next Steps

It is important to remember:

- Most people with TSC suffer few if any complications with their lungs

- Women stand the greatest risk of developing TSC-related tumors and cysts in their lungs, as well as a rare lung disease called lymphangioleiomyomatosis, or LAM

- Approximately 1 to 3 percent of women with TSC develop symptoms of LAM

- The relatively high rate of LAM among adult women compared to men suggests that estrogen may play a role in the disease's development

- Approximately 1 to 3 percent of women with TSC develop symptoms of LAM

- Some symptoms of LAM cause acute medical conditions such as a collapsed lung, or pneumothorax

- TSC specialists recommend routine chest CT scans for all women with TSC beginning prior to the age of 18, or upon diagnosis for women older than 18

- Pregnancy may dramatically increase the risk of serious lung complications among women with LAM. As a result, those who have been diagnosed with LAM should consult with their physicians before getting pregnant

- Physicians of TSC patients should be familiar with TSC-related lung abnormalities

- Physicians should have access to radiologists experienced in identifying lesions associated with LAM

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Glossary

Explanations of common terms you'll encounter when learning about TSC.

Make a Difference for the Herscot Center

Your support is vital to our progress as we move forward into the next generation of teaching, research and clinical care.