Q. What is a coronavirus?

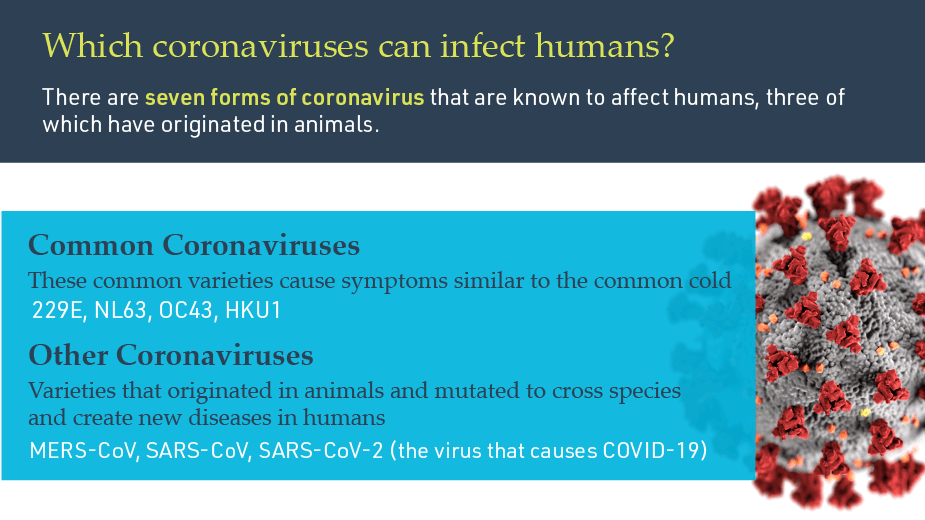

A: Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses that can be found broadly across mammals and birds. They are named after the crown-like spike proteins that surround them. They typically cause limited disease in their host species, but they can occasionally mutate and cross species into humans, causing diseases that range in symptoms and severity.

Q. Why is COVID-19 so infectious?

A: The spikes in the coronavirus are how the virus attaches to their host cell. The stickier the spike, the more efficient the virus is at infecting and spreading. SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has spikes that stick to human cells like Velcro, forming a very strong bond with a receptor called ACE2, which is abundant throughout the human body. These strong bonds mean less SARS-CoV-2 viruses are necessary to start an infection.

Q. What is immunity and how do you test for it?

A: Immunity is when the body is able to resist a particular disease. The standard way of testing for immunity to a virus is to look for antibodies to the virus in the blood (serology tests) following infection.

Q. What are antibodies?

A: Antibodies are proteins in the blood produced in response to an infection. They remain as protection in case the pathogen, an organism that causes disease, invades the body again. They are detectable in the blood approximately five to seven days after symptoms begin to occur, and they are critical to the body's ability to fight off the infectious agent. One of the challenges in identifying immunity to SARS-CoV-2 is that scientists are still working to learn what types and levels of antibodies in the blood are sufficient to protect against reinfection or limit the effects of a second infection by rapidly clearing the virus out of the body.

Q. What is the difference between IgM and IgG antibodies?

A: Immunoglobulin M (IgM) is the first antibody that is produced five to seven days after infection. A high prevalence of IgM antibodies versus other types of antibodies suggests an active infection.

When someone becomes reinfected with the same strain of the virus, B cells that make these IgG antibodies are quickly activated and produce antibodies more rapidly in the secondary response compared to the primary response.

Q. Can antibody tests prove COVID-19 immunity?

A: There is encouraging evidence that previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2 will provide protection from further infection, but it is too early to say whether individuals who have the disease are immune to reinfection, or how long that protection will last. Since the disease has only been infecting humans for less than a year, it will take more time to answer these questions.

Q. What is a vaccine and how does it work?

A: A vaccine is a type of medicine designed to protect against infectious diseases by introducing the body’s immune system to a harmful virus or bacteria in a safe way. This allows the immune system to devise strategies to defeat it, typically by generating antibodies to proteins specific to the disease-causing virus or bacteria.

Q. Why are there so many COVID-19 vaccines in development? Shouldn't there just be one?

A: It is good that there are approximately 135 vaccines now in development worldwide, moving at a pace that we have never seen before. With seven billion people in the world, multiple vaccines are needed so that they can be successful in people of all ages, demographics and medical needs.

Q. How do you determine if a vaccine is successful?

A: There are two questions that scientists must answer in order to successfully develop a vaccine:

- Is there evidence of natural protective immunity to SARS-CoV-2 after an individual has been infected and recovered?

- Is there evidence that a vaccine can induce immunity in subjects who have not been exposed to the virus, and if so, what does that look like in terms of types and numbers of antibodies?

Learn about vaccines that Mass General is developing

Q. Why is it so hard to develop a vaccine?

A: A key challenge in developing vaccines for emerging infectious diseases is that each pathogen uses a different mechanism to infect cells and elicits a different immune response from the body. The majority of vaccines are built from the ground up to address these unique factors and need to undergo rigorous efficacy and safety testing—a process that can typically take up to six years. The majority of vaccines currently being tested and developed rely on previous research addressing other types of infectious diseases.

Q. What are clinical trials and why are they important?

A: Clinical trials are scientific studies designed to test the safety and usefulness of new medical interventions such as treatments, devices, preventative care, screening or diagnostic procedures, and more.

There are four phases of clinical trials that each inform decisions made in the next phase:

- Phase I: Establishing the safety and correct dosage of a treatment

- Phase II: Investigating the efficacy and side effects of a treatment in patients with the disease

- Phase III: Further investigation into efficacy and monitoring of adverse side effects

- Phase IV: Assess the cost-effectiveness and performance of a treatment in real-life scenarios after the treatment has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration

Learn how long each phase can take

Q. How have clinical trials for COVID-19 been moving so quickly?

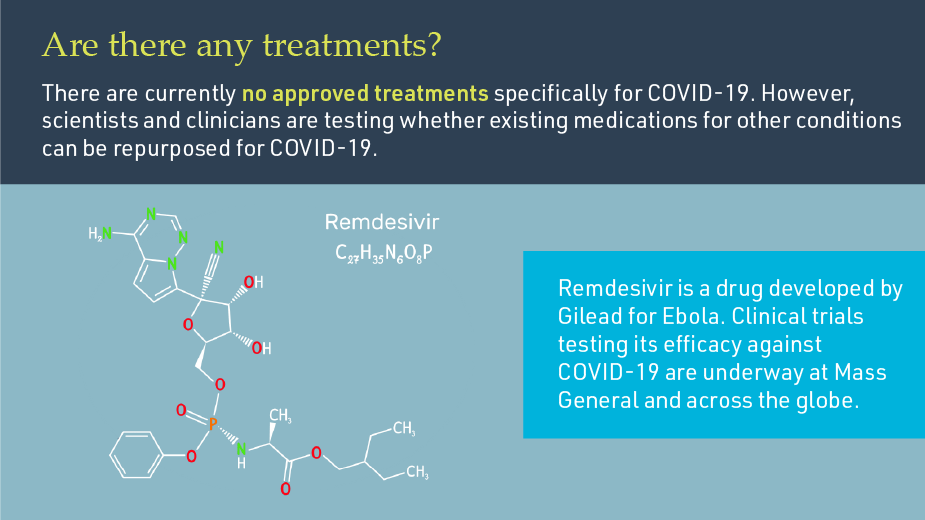

A: In the interest of time for COVID-19, instead of searching for a new treatment, scientists have opted to test treatments that have already been approved for other diseases or have been tested in humans. By starting with a treatment that has been tested extensively in humans, researchers can take advantage of the years of research, preclinical trials and early phase safety trials that have already been conducted on these drugs to move quickly into human patients.

Q. How can you tell if the results of a COVID-19 clinical trial are significant?

A: There are five factors to look at to see if the results from a clinical trial can be considered valid:

- Sample size: The number of patients/participants studied. This is critical because scientists are basing the success of the treatment on how it affects the participants involved

- Placebo: An inactive substance given in the place of a treatment. Testing a new treatment against a placebo gives researchers something to compare their results and helps to eliminate bias in patient-reported outcomes

- Randomization: Assigning treatments to participants at random without considering underlying factors such as disease state, age, weight or medical history. If an experimental treatment was distributed to all participants at random and the health of the experimental group improved (regardless of age), it would be easier to draw more accurate conclusions

- Peer review: A process in which experts in the same field objectively review a scientific study before publication. It is critical to scientific discovery because it helps validate and improve the quality of research

- Blinded studies: Studies that withhold treatment information from patients or researchers to reduce bias. There are two types of blinded studies:

- Single-blind, where researchers know if participants are receiving the treatment or the placebo/standard of care, but participants do not

- Double-blind, where neither participants nor the researchers know who is receiving treatment. This is considered the "gold standard" in clinical trials because it helps reduce participant and researcher bias

Learn more in our Guide to Understanding Clinical Trials, Part II

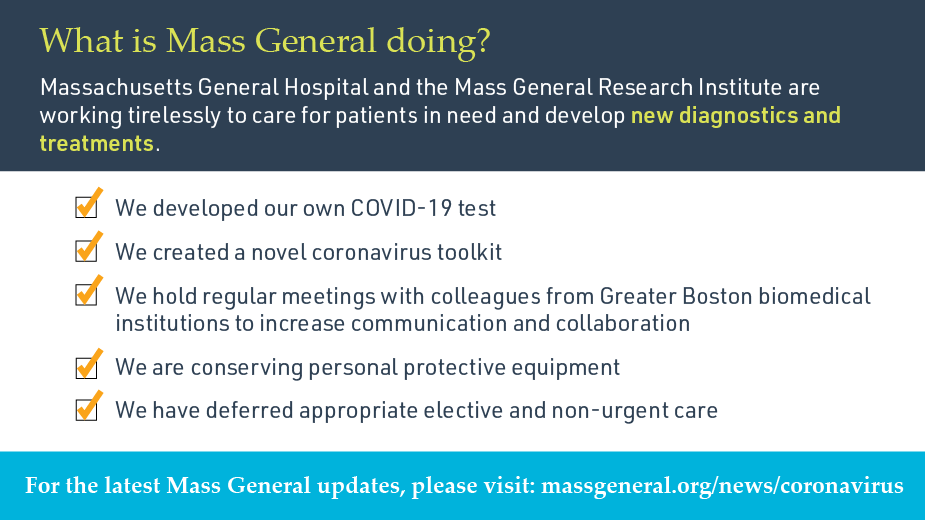

Q. What is Mass General doing to develop a treatment or vaccine for COVID-19?

A: A team from the Vaccine and Immunotherapy Center (VIC) is using a VaxCelerate platform that was designed to quickly develop vaccines in response to emerging infectious diseases to test new vaccine strategies. Mass General is also collaborating with Mass Eye and Ear to test a new gene-therapy based vaccine, and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard is developing a vaccine candidate with support from the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness.

Mass General was the first center in New England to test Remdesivir, which has shown to reduce the amount of time severely ill COVID-19 patients are in the hospital. Mass General clinician-investigators are also conducting clinical trials to test a variety of treatment strategies for the disease, including antiviral, anti-inflammatory and anti-coagulant drugs.